James Watson

James Watson | |

|---|---|

Watson in 2012 | |

| Born | James Dewey Watson April 6, 1928[9] Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Lewis (m. 1968) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Genetics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | The Biological Properties of X-Ray Inactivated Bacteriophage (1951) |

| Doctoral advisor | Salvador Luria |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students |

|

| Signature | |

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in Nature proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule.[10] Watson, Crick and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material". He later drew criticism with pronouncements on genetics, race and intelligence that were regarded as racist.[11][12]

Watson earned degrees at the University of Chicago (BS, 1947) and Indiana University (PhD, 1950). Following a post-doctoral year at the University of Copenhagen with Herman Kalckar and Ole Maaløe, Watson worked at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory in England, where he first met his future collaborator Francis Crick. From 1956 to 1976, Watson was on the faculty of the Harvard University Biology Department, promoting research in molecular biology.

From 1968, Watson served as director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), greatly expanding its level of funding and research. At CSHL, he shifted his research emphasis to the study of cancer, along with making it a world-leading research center in molecular biology. In 1994, he started as president and served for 10 years. He was then appointed chancellor, serving until he resigned in 2007 after making comments claiming that there is a genetic link between intelligence and race. In 2019, following the broadcast of a documentary in which Watson reiterated these views on race and genetics, CSHL revoked his honorary titles and severed all ties with him.

Watson has written many science books, including the textbook Molecular Biology of the Gene (1965) and his bestselling book The Double Helix (1968). Between 1988 and 1992, Watson was associated with the National Institutes of Health, helping to establish the Human Genome Project, which completed the task of mapping the human genome in 2003.

Early life and education

[edit]Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, as the only son of Jean (née Mitchell) and James D. Watson, a businessman descended mostly from colonial English immigrants to America.[13] His mother's father, Lauchlin Mitchell, a tailor, was from Glasgow, Scotland, and her mother, Lizzie Gleason, was the child of parents from County Tipperary, Ireland.[14] His mother was a modestly religious Catholic and his father an Episcopalian who had lost his belief in God.[15] Watson was raised Catholic, but he later described himself as "an escapee from the Catholic religion".[16] Watson said, "The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was that my father didn't believe in God."[17] By age 11, Watson stopped attending mass and embraced the "pursuit of scientific and humanistic knowledge."[15]

Watson grew up on the South Side of Chicago and attended public schools, including Horace Mann Elementary School and South Shore High School.[13][18] He was fascinated with bird watching, a hobby shared with his father,[19] so he considered majoring in ornithology.[20] Watson appeared on Quiz Kids, a popular radio show that challenged bright youngsters to answer questions.[21] Thanks to the liberal policy of university president Robert Hutchins, he enrolled at the University of Chicago, where he was awarded a tuition scholarship, at the age of 15.[13][20][22] Among his professors was Louis Leon Thurstone from whom Watson learned about factor analysis, which he would later reference on his controversial views on race.[23]

After reading Erwin Schrödinger's book, What Is Life? in 1946, Watson changed his professional ambitions from the study of ornithology to genetics.[24] Watson earned his BS degree in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1947.[20] In his autobiography, Avoid Boring People, Watson described the University of Chicago as an "idyllic academic institution where he was instilled with the capacity for critical thought and an ethical compulsion not to suffer fools who impeded his search for truth", in contrast to his description of later experiences. In 1947 Watson left the University of Chicago to become a graduate student at Indiana University, attracted by the presence at Bloomington of the 1946 Nobel Prize winner Hermann Joseph Muller, who in crucial papers published in 1922, 1929, and in the 1930s had laid out all the basic properties of the heredity molecule that Schrödinger presented in his 1944 book.[25] He received his PhD degree from Indiana University in 1950; Salvador Luria was his doctoral advisor.[20][26]

Career and research

[edit]Luria, Delbrück, and the Phage Group

[edit]Originally, Watson was drawn into molecular biology by the work of Salvador Luria. Luria eventually shared the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the Luria–Delbrück experiment, which concerned the nature of genetic mutations. He was part of a distributed group of researchers who were making use of the viruses that infect bacteria, called bacteriophages. He and Max Delbrück were among the leaders of this new "Phage Group", an important movement of geneticists from experimental systems such as Drosophila towards microbial genetics. Early in 1948, Watson began his PhD research in Luria's laboratory at Indiana University.[26] That spring, he met Delbrück first in Luria's apartment and again that summer during Watson's first trip to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL).[27][28]

The Phage Group was the intellectual medium where Watson became a working scientist. Importantly, the members of the Phage Group sensed that they were on the path to discovering the physical nature of the gene. In 1949, Watson took a course with Felix Haurowitz that included the conventional view of that time: that genes were proteins and able to replicate themselves.[29] The other major molecular component of chromosomes, DNA, was widely considered to be a "stupid tetranucleotide", serving only a structural role to support the proteins.[30] Even at this early time, Watson, under the influence of the Phage Group, was aware of the Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment, which suggested that DNA was the genetic molecule. Watson's research project involved using X-rays to inactivate bacterial viruses.[31]

Watson then went to Copenhagen University in September 1950 for a year of postdoctoral research, first heading to the laboratory of biochemist Herman Kalckar.[13] Kalckar was interested in the enzymatic synthesis of nucleic acids, and he wanted to use phages as an experimental system. Watson wanted to explore the structure of DNA, and his interests did not coincide with Kalckar's.[32] After working part of the year with Kalckar, Watson spent the remainder of his time in Copenhagen conducting experiments with microbial physiologist Ole Maaløe, then a member of the Phage Group.[33]

The experiments, which Watson had learned of during the previous summer's Cold Spring Harbor phage conference, included the use of radioactive phosphate as a tracer to determine which molecular components of phage particles actually infect the target bacteria during viral infection.[32] The intention was to determine whether protein or DNA was the genetic material, but upon consultation with Max Delbrück,[32] they determined that their results were inconclusive and could not specifically identify the newly labeled molecules as DNA.[34] Watson never developed a constructive interaction with Kalckar, but he did accompany Kalckar to a meeting in Italy, where Watson saw Maurice Wilkins talk about X-ray diffraction data for DNA.[13] Watson was now certain that DNA had a definite molecular structure that could be elucidated.[35]

In 1951, the chemist Linus Pauling in California published his model of the amino acid alpha helix, a result that grew out of Pauling's efforts in X-ray crystallography and molecular model building. After obtaining some results from his phage and other experimental research[36] conducted at Indiana University, Statens Serum Institut (Denmark), CSHL, and the California Institute of Technology, Watson now had the desire to learn to perform X-ray diffraction experiments so he could work to determine the structure of DNA. That summer, Luria met John Kendrew,[37] and he arranged for a new postdoctoral research project for Watson in England.[13] In 1951 Watson visited the Stazione Zoologica 'Anton Dohrn' in Naples.[38]

Identifying the double helix

[edit]

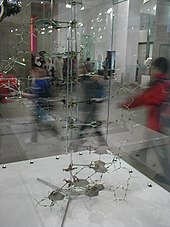

In mid-March 1953, Watson and Crick deduced the double helix structure of DNA.[13] Crucial to their discovery were the experimental data collected at King's College London—mainly by Rosalind Franklin for which they did not provide proper attribution.[39][40] Sir Lawrence Bragg,[41] the director of the Cavendish Laboratory (where Watson and Crick worked), made the original announcement of the discovery at a Solvay conference on proteins in Belgium on April 8, 1953; it went unreported by the press. Watson and Crick submitted a paper entitled "Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid" to the scientific journal Nature, which was published on April 25, 1953.[42] Bragg gave a talk at the Guy's Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday, May 14, 1953, which resulted in a May 15, 1953, article by Ritchie Calder in the London newspaper News Chronicle, entitled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life".

Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Dorothy Hodgkin, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton were some of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Crick and Watson; at the time, they were working at Oxford University's chemistry department. All were impressed by the new DNA model, especially Brenner, who subsequently worked with Crick at Cambridge in the Cavendish Laboratory and the new Laboratory of Molecular Biology. According to the late Beryl Oughton, later Rimmer, they all travelled together in two cars once Dorothy Hodgkin announced to them that they were off to Cambridge to see the model of the structure of DNA.[43]

The Cambridge University student newspaper Varsity ran its own short article on the discovery on Saturday, May 30, 1953. Watson subsequently presented a paper on the double-helical structure of DNA at the 18th Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Viruses in early June 1953, six weeks after the publication of the Watson and Crick paper in Nature. Many at the meeting had not yet heard of the discovery. The 1953 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium was the first opportunity for many to see the model of the DNA double helix. Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for their research on the structure of nucleic acids.[13][44][45] Rosalind Franklin had died in 1958 and was therefore ineligible for nomination.[39] The publication of the double helix structure of DNA has been described as a turning point in science; understanding of life was fundamentally changed and the modern era of biology began.[46]

Interactions with Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling

[edit]Watson and Crick's use of DNA X-ray diffraction data collected by Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling has attracted scrutiny. It has been argued that Watson and his colleagues did not properly acknowledge colleague Rosalind Franklin for her contributions to the discovery of the double helix structure.[40][47] Robert P. Crease notes that "Such stingy behaviour may not be unknown, or even uncommon, among scientists".[48] Franklin's high-quality X-ray diffraction patterns of DNA were unpublished results, which Watson and Crick used without her knowledge or consent in their construction of the double helix model of DNA.[47][39][49] Franklin's results provided estimates of the water content of DNA crystals and these results were consistent with the two sugar-phosphate backbones being on the outside of the molecule. Franklin told Crick and Watson that the backbones had to be on the outside; before then, Linus Pauling and Watson and Crick had erroneous models with the chains inside and the bases pointing outwards.[25] Her identification of the space group for DNA crystals revealed to Crick that the two DNA strands were antiparallel.

The X-ray diffraction images collected by Gosling and Franklin provided the best evidence for the helical nature of DNA. Watson and Crick had three sources for Franklin's unpublished data:

- Her 1951 seminar, attended by Watson;[50]

- Discussions with Wilkins,[51] who worked in the same laboratory with Franklin;

- A research progress report that was intended to promote coordination of Medical Research Council-supported laboratories.[52] Watson, Crick, Wilkins and Franklin all worked in MRC laboratories.

In a 1954 article, Watson and Crick acknowledged that, without Franklin's data, "the formulation of our structure would have been most unlikely, if not impossible".[53] In The Double Helix, Watson later admitted that "Rosy, of course, did not directly give us her data. For that matter, no one at King's realized they were in our hands". In recent years, Watson has garnered controversy in the popular and scientific press for his "misogynist treatment" of Franklin and his failure to properly attribute her work on DNA.[40] According to one critic, Watson's portrayal of Franklin in The Double Helix was negative, giving the impression that she was Wilkins' assistant and was unable to interpret her own DNA data.[54] Watson's accusation was indefensible since Franklin told Crick and Watson that the helix backbones had to be on the outside.[25] From a 2003 piece by Brenda Maddox in Nature:[40]

Other comments dismissive of "Rosy" in Watson's book caught the attention of the emerging women's movement in the late 1960s. "Clearly Rosy had to go or be put in her place ... Unfortunately Maurice could not see any decent way to give Rosy the boot". And, "Certainly a bad way to go out into the foulness of a ... November night was to be told by a woman to refrain from venturing an opinion about a subject for which you were not trained."

Robert P. Crease remarks that "[Franklin] was close to figuring out the structure of DNA, but did not do it. The title of 'discoverer' goes to those who first fit the pieces together".[48] Jeremy Bernstein rejects that Franklin was a "victim" and states that "[Watson and Crick] made the double-helix scheme work. It is as simple as that".[48] Matthew Cobb and Nathaniel C. Comfort write that "Franklin was no victim in how the DNA double helix was solved" but that she was "an equal contributor to the solution of the structure".[53]

A review of the correspondence from Franklin to Watson, in the archives at CSHL, revealed that the two scientists later exchanged constructive scientific correspondence. Franklin consulted with Watson on her tobacco mosaic virus RNA research. Franklin's letters were framed with the normal and unremarkable forms of address, beginning with "Dear Jim", and concluding with "Best Wishes, Yours, Rosalind". Each of the scientists published their own unique contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA in separate articles, and all of the contributors published their findings in the same volume of Nature. These classic molecular biology papers are identified as: Watson J. D. and Crick F. H. C. "A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid". Nature 171, 737–738 (1953);[42] Wilkins M. H. F., Stokes A. R. & Wilson H. R. "Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids". Nature 171, 738–740 (1953);[55] Franklin R. and Gosling R. G. "Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate". Nature 171, 740–741 (1953).[56]

Harvard University

[edit]In 1956, Watson accepted a position in the biology department at Harvard University. His work at Harvard focused on RNA and its role in the transfer of genetic information.[57]

Watson championed a switch in focus for the school from classical biology to molecular biology, stating that disciplines such as ecology, developmental biology, taxonomy, physiology, etc. had stagnated and could progress only once the underlying disciplines of molecular biology and biochemistry had elucidated their underpinnings, going so far as to discourage their study by students.

Watson continued to be a member of the Harvard faculty until 1976, even though he took over the directorship of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1968.[57]

During his tenure at Harvard, Watson participated in a protest against the Vietnam War, leading a group of 12 biologists and biochemists calling for "the immediate withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam".[58] In 1975, on the thirtieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, Watson was one of over 2000 scientists and engineers who spoke out against nuclear proliferation to President Gerald Ford, arguing that there was no proven method for the safe disposal of radioactive waste, and that nuclear plants were a security threat due to the possibility of terrorist theft of plutonium.[59]

Watson's first textbook, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, used the concept of heads—brief declarative subheadings.[60] His next textbook was Molecular Biology of the Cell, in which he coordinated the work of a group of scientist-writers. His third was Recombinant DNA, which described the ways in which genetic engineering has brought new information about how organisms function.

Publishing The Double Helix

[edit]In 1968, Watson wrote The Double Helix,[61] listed by the board of the Modern Library as number seven in their list of 100 Best Nonfiction books.[62] The book details the story of the discovery of the structure of DNA, as well as the personalities, conflicts and controversy surrounding their work, and includes many of his private emotional impressions at the time. Watson's original title was to have been "Honest Jim".[63] Controversy surrounded the publication of the book. Watson's book was originally to be published by the Harvard University Press, but Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, among others, objected. Watson's home university dropped the project and the book was commercially published.[64][65] In an interview with Anne Sayre for her book, Rosalind Franklin and DNA (published in 1975 and reissued in 2000), Francis Crick said that he regarded Watson's book as a "contemptible pack of damned nonsense".[66]

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

In 1968, Watson became the director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). Between 1970 and 1972, the Watsons' two sons were born, and by 1974, the young family made Cold Spring Harbor their permanent residence. Watson served as the laboratory's director and president for about 35 years, and later he assumed the role of chancellor and then chancellor emeritus.

In his roles as director, president, and chancellor, Watson led CSHL to articulate its present-day mission, "dedication to exploring molecular biology and genetics in order to advance the understanding and ability to diagnose and treat cancers, neurological diseases, and other causes of human suffering."[67] CSHL substantially expanded both its research and its science educational programs under Watson's direction. He is credited with "transforming a small facility into one of the world's great education and research institutions. Initiating a program to study the cause of human cancer, scientists under his direction have made major contributions to understanding the genetic basis of cancer."[68] In a retrospective summary of Watson's accomplishments there, Bruce Stillman, the laboratory's president, said, "Jim Watson created a research environment that is unparalleled in the world of science."[68]

In 2007, Watson said, "I turned against the left wing because they don't like genetics, because genetics implies that sometimes in life we fail because we have bad genes. They want all failure in life to be due to the evil system."[69]

Human Genome Project

[edit]

In 1990, Watson was appointed as the head of the Human Genome Project at the National Institutes of Health, a position he held until April 10, 1992.[70] Watson left the Genome Project after conflicts with the new NIH Director, Bernadine Healy. Watson was opposed to Healy's attempts to acquire patents on gene sequences, and any ownership of the "laws of nature". Two years before stepping down from the Genome Project, he had stated his own opinion on this long and ongoing controversy which he saw as an illogical barrier to research; he said, "The nations of the world must see that the human genome belongs to the world's people, as opposed to its nations." He left within weeks of the 1992 announcement that the NIH would be applying for patents on brain-specific cDNAs.[71] (The issue of the patentability of genes has since been resolved in the US by the US Supreme Court; see Association for Molecular Pathology v. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.)

In 1994, Watson became president of CSHL. Francis Collins took over the role as director of the Human Genome Project.

Watson was quoted in The Sunday Telegraph in 1997 as stating: "If you could find the gene which determines sexuality and a woman decides she doesn't want a homosexual child, well, let her."[72] The biologist Richard Dawkins wrote a letter to The Independent claiming that Watson's position was misrepresented by The Sunday Telegraph article, and that Watson would equally consider the possibility of having a heterosexual child to be just as valid as any other reason for abortion, to emphasise that Watson is in favor of allowing choice.[73]

On the issue of obesity, Watson was quoted in 2000, saying: "Whenever you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you're not going to hire them."[74]

Watson has repeatedly supported genetic screening and genetic engineering in public lectures and interviews, arguing that stupidity is a disease and the "really stupid" bottom 10% of people should be cured.[75] He has also suggested that beauty could be genetically engineered, saying in 2003, "People say it would be terrible if we made all girls pretty. I think it would be great."[75][76]

In 2007, Watson became the second person[77] to publish his fully sequenced genome online,[78] after it was presented to him on May 31, 2007, by 454 Life Sciences Corporation[79] in collaboration with scientists at the Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine. Watson was quoted as saying, "I am putting my genome sequence on line to encourage the development of an era of personalized medicine, in which information contained in our genomes can be used to identify and prevent disease and to create individualized medical therapies".[80][81][82]

Later life

[edit]In 2014, Watson published a paper in The Lancet suggesting that biological oxidants may have a different role than is thought in diseases including diabetes, dementia, heart disease and cancer. For example, type 2 diabetes is usually thought to be caused by oxidation in the body that causes inflammation and kills off pancreatic cells. Watson thinks the root of that inflammation is different: "a lack of biological oxidants, not an excess", and discusses this in detail. One critical response was that the idea was neither new nor worthy of merit, and that The Lancet published Watson's paper only because of his name.[83] Other scientists have expressed their support for his hypothesis and have proposed that it can also be expanded to why a lack of oxidants can result in cancer and its progression.[84]

In 2014, Watson sold his Nobel Prize medal to raise money after complaining of being made an "unperson" following controversial statements he had made.[85] Part of the funds raised by the sale went to support scientific research.[86] The medal sold at auction at Christie's in December 2014 for US$4.1 million. Watson intended to contribute the proceeds to conservation work in Long Island and to funding research at Trinity College, Dublin.[87][88] He was the first living Nobel recipient to auction a medal.[89] The medal was later returned to Watson by the purchaser, Alisher Usmanov.[90]

Notable former students

[edit]Several of Watson's former doctoral students subsequently became notable in their own right including, Mario Capecchi,[3] Bob Horvitz, Peter B. Moore and Joan Steitz.[4] Besides numerous PhD students, Watson also supervised postdoctoral researchers and other interns including Ewan Birney,[5] Ronald W. Davis, Phillip Allen Sharp (postdoc), John Tooze (postdoc)[7][8] and Richard J. Roberts (postdoc).[6]

Other affiliations

[edit]Watson is a former member of the Board of Directors of United Biomedical, Inc., founded by Chang Yi Wang. He held the position for six years and retired from the board in 1999.[91]

In January 2007, Watson accepted the invitation of Leonor Beleza, president of the Champalimaud Foundation, to become the head of the foundation's scientific council, an advisory organ.[92][93]

In March 2017, Watson was named head consultant of the Cheerland Investment Group, a Chinese investment company which sponsored his trip.[citation needed][94]

Watson has been an institute adviser for the Allen Institute for Brain Science.[95][96]

Avoid Boring People

[edit]

Watson has had disagreements with Craig Venter regarding his use of EST fragments while Venter worked at NIH. Venter went on to found Celera genomics and continued his feud with Watson. Watson was quoted as calling Venter "Hitler".[97]

In his 2007 memoir, Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science, Watson describes his academic colleagues as "dinosaurs", "deadbeats", "fossils", "has-beens", "mediocre", and "vapid".[98] Steve Shapin in Harvard Magazine noted that Watson had written an unlikely "Book of Manners", telling about the skills needed at different times in a scientist's career; he wrote Watson was known for aggressively pursuing his own goals at the university. E. O. Wilson once described Watson as "the most unpleasant human being I had ever met", but in a later TV interview said that he considered them friends and their rivalry at Harvard "old history" (when they had competed for funding in their respective fields).[99][100]

In the epilogue to the memoir Avoid Boring People, Watson alternately attacks and defends former Harvard University president Lawrence Summers, who stepped down in 2006 due in part to his remarks about women and science.[101] Watson also states in the epilogue, "Anyone sincerely interested in understanding the imbalance in the representation of men and women in science must reasonably be prepared at least to consider the extent to which nature may figure, even with the clear evidence that nurture is strongly implicated."[76][98]

Comments on race

[edit]At a conference in 2000, Watson suggested a link between skin color and sex drive, hypothesizing that dark-skinned people have stronger libidos.[74][102] His lecture argued that extracts of melanin—which gives skin its color—had been found to boost subjects' sex drive. "That's why you have Latin lovers", he said, according to people who attended the lecture. "You've never heard of an English lover. Only an English Patient."[103] He has also said that stereotypes associated with racial and ethnic groups have a genetic basis: Jews being intelligent, Chinese being intelligent but not creative because of selection for conformity, and Indians being servile because of selection under caste endogamy.[104] Regarding intelligence differences between blacks and whites, Watson has asserted that "all our social policies are based on the fact that their (blacks) intelligence is the same as ours (whites) – whereas all the testing says not really ... people who have to deal with black employees find this not true."[105]

Watson has repeatedly asserted that differences in average measured IQ between blacks and whites are due to genetics.[106][107][11] In early October 2007, he was interviewed by Charlotte Hunt-Grubbe at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). He discussed his view that Africans are less intelligent than Westerners.[108][109][12] Watson said his intention was to promote science, not racism, but some UK venues canceled his appearances,[110] and he canceled the rest of his tour.[111][112][113][114] An editorial in Nature said that his remarks were "beyond the pale" but expressed a wish that the tour had not been canceled so that Watson would have had to face his critics in person, encouraging scientific discussion on the matter.[115] Because of the controversy, the board of trustees at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory suspended Watson's administrative responsibilities.[116] Watson issued an apology,[117] then retired at the age of 79 from CSHL from what the lab called "nearly 40 years of distinguished service".[68][118] Watson attributed his retirement to his age and to circumstances that he could never have anticipated or desired.[119][120][121]

In 2008, Watson was appointed chancellor emeritus of CSHL[122][123] but continued to advise and guide project work at the laboratory.[124] In a BBC documentary that year, Watson said he did not see himself as a racist.[125]

In January 2019, following the broadcast of a television documentary made the previous year in which he repeated his views about race and genetics, CSHL revoked honorary titles that it had awarded to Watson and cut all remaining ties with him.[126][127][128] Watson did not respond to the developments.[129]

Personal life

[edit]Watson is an atheist.[17][130] In 2003, he was one of 22 Nobel Laureates who signed the Humanist Manifesto.[131] Watson wrote in Time that he contributed $1,000 to Bernie Sanders' 2016 presidential campaign.[15]

Marriage and family

[edit]Watson married Elizabeth Lewis in 1968.[9] They have two sons, Rufus Robert Watson (b. 1970) and Duncan James Watson (b. 1972). Watson sometimes talks about his son Rufus, who has schizophrenia, seeking to encourage progress in the understanding and treatment of mental illness by determining how genetics contributes to it.[124]

Awards and honors

[edit]

Watson has won numerous awards, including:

- Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research, 1960[132]

- Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Achievement in the Sciences (2001)[133]

- Copley Medal of the Royal Society, 1993[1]

- CSHL Double Helix Medal Honoree, 2008[134]

- Eli Lilly Award in Biological Chemistry, 1960

- EMBO Membership in 1985[135]

- Gairdner Foundation International Award, 2002

- Honorary Member of Royal Irish Academy, 2005

- Honorary Fellow, the Hastings Center, an independent bioethics research institution[136]

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE), 2002[137]

- Irish America Hall of Fame, inducted March 2011[138]

- John J. Carty Award in molecular biology from the National Academy of Sciences[139]

- Liberty Medal, 2000[140]

- Lomonosov Gold Medal, 1994

- Lotos Club Medal of Merit, 2004

- National Medal of Science, 1997[141]

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1962[13]

- Othmer Gold Medal (2005)[142][143]

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1977[144]

- Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement, 1986[145]

Honorary degrees received

[edit]- DSc, University of Chicago, US, 1961

- DSc, Indiana University, US, 1963

- LLD, University of Notre Dame, US, 1965

- DSc, Long Island University (CW Post), US, 1970

- DSc, Adelphi University, US, 1972

- DSc, Brandeis University, US, 1973

- DSc, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, US, 1974

- DSc, Hofstra University, US, 1976

- DSc, Harvard University, US, 1978

- DSc, Rockefeller University, US, 1980

- DSc, Clarkson College of Technology, US, 1981

- DSc, SUNY at Farmingdale, US, 1983

- MD, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1986

- DSc, Rutgers University, US, 1988

- DSc, Bard College, US, 1991

- DSc, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa, 1993

- DSc, Fairfield University, US, 1993

- DSc, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1993

- DrHC, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic, 1998

- ScD, University of Dublin, Ireland, 2001[146]

Professional and honorary affiliations

[edit]- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- American Association for Cancer Research

- American Philosophical Society

- American Society of Biological Chemists

- Athenaeum Club, London, member

- Cambridge University, Honorary Fellow, Clare College, Cambridge[9]

- Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Chancellor Emeritus; Honorary Trustee; Oliver R. Grace Professor Emeritus (all revoked in 2019)[147][148]

- European Molecular Biology Organization, member since 1985[135]

- National Academy of Sciences

- Oxford University, Newton-Abraham Visiting Professor

- Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters

- Royal Society, Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) since 1981[1]

- Russian Academy of Sciences

See also

[edit]- Behavioral genetics

- History of molecular biology

- History of RNA biology

- Life Story – 1987 BBC docudrama about Watson and Crick's discovery of DNA structure

- List of RNA biologists

- Nobel disease

- Predictive medicine

- Whole genome sequencing

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Anon (1981). "Dr James Watson ForMemRS". royalsociety.org. London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from the royalsociety.org website where:

"All text published under the heading 'Biography' on Fellow profile pages is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License." --"Royal Society Terms, conditions and policies". Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Copley Medal". Royal Society website. The Royal Society. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Capecchi, Mario (1967). On the Mechanism of Suppression and Polypeptide Chain Initiation (PhD thesis). Harvard University. ProQuest 302261581.

- ^ a b Steitz, J (2011). "Joan Steitz: RNA is a many-splendored thing. Interview by Caitlin Sedwick". The Journal of Cell Biology. 192 (5): 708–709. doi:10.1083/jcb.1925pi. PMC 3051824. PMID 21383073.

- ^ a b Hopkin, Karen (June 2005). "Bring Me Your Genomes: The Ewan Birney Story". The Scientist. 19 (11): 60.

- ^ a b Anon (1993). "Richard J. Roberts – Biographical". nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Ferry, Georgina (2014). EMBO in perspective: a half-century in the life sciences (PDF). Heidelberg: European Molecular Biology Organization. p. 145. ISBN 978-3-00-046271-9. OCLC 892947326. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Ferry, Georgina (2014). "History: Fifty years of EMBO". Nature. 511 (7508). London: 150–151. doi:10.1038/511150a. PMID 25013879.

- ^ a b c "Watson, Prof. James Dewey". Who's Who. Vol. 2015 (online Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Watson, James; Crick, Francis (April 25, 1953). "Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid". Nature. 171 (4356): 737–738. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..737W. doi:10.1038/171737a0. PMID 13054692.

- ^ a b Harmon, Amy (January 1, 2019). "James Watson Had a Chance to Salvage His Reputation on Race. He Made Things Worse." The New York Times. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ a b Peck, Sally (October 17, 2007). "James Watson suspended over racism claims". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "James Watson, The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962". NobelPrize.org. 1964. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ Randerson, James (October 25, 2007). "Watson retires". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c Watson, James (March 25, 2016). "Nobel Scientist: I Place My Faith in Human Gods". TIME. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Watson, J. D. (2003). Genes, Girls, and Gamow: After the Double Helix. New York: Vintage. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-375-72715-3. OCLC 51338952.

- ^ a b "Discover Dialogue: Geneticist James Watson". Discover. July 2003.

The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was that my father didn't believe in God

- ^ Cullen, Katherine E. (2006). Biology: the people behind the science. New York: Chelsea House. p. 133. ISBN 0-8160-5461-4.

- ^ Watson, James. "James Watson (Oral History)". Web of Stories. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Cullen, Katherine E. (2006). Biology: the people behind the science. New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 0-8160-5461-4.

- ^ Samuels, Rich. "The Quiz Kids". Broadcasting in Chicago, 1921–1989. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ "Nobel laureate, Chicago native James Watson to receive University of Chicago. Alumni Medal June 2". The University of Chicago News Office. June 1, 2007. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2021). The Code Breaker. Simon & Schuster. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-9821-1585-2.

- ^ Friedberg, Errol C. (2005). The Writing Life of James D. Watson. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-700-6. Reviewed by Lewis Wolpert, Nature, (2005) 433:686–687.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, James (2008). In pursuit of the gene : from Darwin to DNA. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674026704.

- ^ a b Watson, James (1951). The Biological Properties of X-Ray Inactivated Bacteriophage (PhD thesis). Indiana University. ProQuest 302021835.

- ^ Watson, James D.; Berry, Andrew (2003). DNA : the secret of life (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0375415463.

- ^ Watson, James D. (2012). "James D. Watson Chancellor Emeritus". Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Putnum, Frank W. (1994). Biographical Memoirs – Felix Haurowitz (volume 64 ed.). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 134–163. ISBN 0-309-06978-5.

Among [Haurowitz's] students was Jim Watson, then a graduate student of Luria.

- ^ Stewart, Ian (2011). "The structure of DNA". The Mathematics of Life. Basic Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-465-02238-0.

- ^ Watson, J. D. (1950). "The properties of x-ray inactivated bacteriophage. I. Inactivation by direct effect". Journal of Bacteriology. 60 (6): 697–718. doi:10.1128/JB.60.6.697-718.1950. PMC 385941. PMID 14824063.

- ^ a b c McElheny, Victor K. (2004). Watson and DNA: Making a Scientific Revolution. Basic Books. p. 28. ISBN 0-7382-0866-3.

- ^ Putnam, F. W. (1993). "Growing up in the golden age of protein chemistry". Protein Science. 2 (9): 1536–1542. doi:10.1002/pro.5560020919. PMC 2142464. PMID 8401238.

- ^ Maaløe, O.; Watson, J. D. (1951). "The Transfer of Radioactive Phosphorus from Parental to Progeny Phage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 37 (8): 507–513. Bibcode:1951PNAS...37..507M. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.8.507. PMC 1063410. PMID 16578386.

- ^ Judson, Horace Freeland (1979). "2". The eighth day of creation: makers of the revolution in biology (1st Touchstone ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22540-5.

- ^ "PDS SSO". Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Holmes, K. C. (2001). "Sir John Cowdery Kendrew. March 24, 1917 – August 23, 1997: Elected F.R.S. 1960". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 47: 311–332. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2001.0018. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0028-EC77-7. PMID 15124647.

- ^ "Il Mattino". ilmattino.it. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c "James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, and Rosalind Franklin". Science History Institute. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Maddox, Brenda (January 2003). "The double helix and the 'wronged heroine'". Nature. 421 (6921): 407–408. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..407M. doi:10.1038/nature01399. PMID 12540909.

- ^ Phillips, D. (1979). "William Lawrence Bragg. 31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 25: 74–143. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1979.0003. JSTOR 769842. S2CID 119994416.

- ^ a b Watson, J. D.; Crick, F. H. (1953). "A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acids" (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 737–738. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..737W. doi:10.1038/171737a0. PMID 13054692. S2CID 4253007.

- ^ Olby, Robert (2009). "10". Francis Crick: hunter of life's secrets. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-87969-798-3.

- ^ Judson, H. F. (October 20, 2003). "No Nobel Prize for Whining". New York Times. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ^ Watson, James. "Nobel Lecture December 11, 1962 The Involvement of RNA in the Synthesis of Proteins". 11 December 1962. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Rutherford, Adam (April 24, 2013). "DNA double helix: discovery that led to 60 years of biological revolution". The Guardian. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Stasiak, Andrzej (March 15, 2001). "Rosalind Franklin". EMBO Reports. 2 (3). National Institutes of Health: 181. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve037. PMC 1083834.

- ^ a b c Crease, Robert P. (2003). "The Rosalind Franklin question". Physics World. 16 (3): 17. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/16/3/23. ISSN 0953-8585.

- ^ Judson, H. F. (1996). The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, chapter 3. ISBN 0-87969-478-5.

- ^ Cullen, Katherine E. (2006). Biology: the people behind the science. New York: Chelsea House. p. 136. ISBN 0-8160-5461-4.

- ^ Cullen, Katherine E. (2006). Biology: the people behind the science. New York: Chelsea House. p. 140. ISBN 0-8160-5461-4.

- ^ Stocklmayer, Susan M.; Gore, Michael M.; Bryant, Chris (2001). Science Communication in Theory and Practice. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 79. ISBN 1-4020-0131-2.

- ^ a b Cobb, Matthew; Comfort, Nathaniel (2023). "What Rosalind Franklin truly contributed to the discovery of DNA's structure". Nature. 616 (7958): 657–660. Bibcode:2023Natur.616..657C. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-01313-5. PMID 37100935.

- ^ Elkin, L. O. (2003). "Franklin and the Double Helix". Physics Today. 56 (3): 42. Bibcode:2003PhT....56c..42E. doi:10.1063/1.1570771.

- ^ Wilkins, M. H. F.; Stokes, A. R.; Wilson, H. R. (1953). "Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids" (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 738–740. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..738W. doi:10.1038/171738a0. PMID 13054693. S2CID 4280080.

- ^ Franklin, R.; Gosling, R. G. (1953). "Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate" (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 740–741. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..740F. doi:10.1038/171740a0. PMID 13054694. S2CID 4268222.

- ^ a b "The DNA molecule is shaped like a twisted ladder". DNA from the beginning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "Faculty Support Grows For Anti-War Proposal", The Harvard Crimson, October 3, 1969.

- ^ "Three Harvard Scientists Lead Call to Stop Nuclear Reactors", The Harvard Crimson, August 5, 1975.

- ^ Watson, J. D. (1965). Molecular biology of the gene. New York: W. A. Benjamin.

- ^ Watson, J. D. (1968). The double helix: a personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ^ "100 Best Nonfiction: The Board's List". Modern Library. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Rutherford, Adam (December 1, 2014). "He may have unravelled DNA, but James Watson deserves to be shunned". The Guardian. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Watson's 1968 autobiographical account, The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. For an edition which contains critical responses, book reviews, and copies of the original scientific papers, see James D. Watson, The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA, Norton Critical Edition, Gunther Stent, ed. (New York: Norton, 1980).

- ^ Watson, James D. (2012). Witkowski, Jan; Gann, Alexander (eds.). The annotated and illustrated double helix (1st Simon & Schuster hardcover ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-476715-49-0.

- ^ Sayre, Anne (2000). Rosalind Franklin and DNA. New York: Norton. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-393-32044-2. OCLC 45105026.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Gerald (September 8, 2010). "Honorary Doctorate awarded to Nobel Laureate: Text of the Introductory Address". University College, Cork, Ireland. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Dr. James D. Watson Retires as Chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory" (Press release). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ John H. Richardson (October 19, 2007). "Discovery of DNA structure – James Watson on the Double Helix". Esquire. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ "National Human Genome Research Institute – Organization – The NIH Almanac – National Institutes of Health (NIH)". Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Pollack, R. 1994. Signs of Life: The Language and Meanings of DNA. Houghton Mifflin, p. 95. ISBN 0-395-73530-0.

- ^ Macdonald, V. "Abort babies with gay genes, says Nobel winner", The Telegraph, February 16, 1997. Retrieved on October 24, 2007.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (February 19, 1997). "Letter: Women to decide on gay abortion". The Independent. London. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Abate, T. "Nobel Winner's Theories Raise Uproar in Berkeley Geneticist's views strike many as racist, sexist", San Francisco Chronicle, November 13, 2000. Retrieved on October 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, S. "Stupidity should be cured, says DNA discoverer", New Scientist, February 28, 2003. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Williams, Susan P. (November 8, 2007). "The Foot-in-Mouth Gene". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Genome of DNA Discoverer Is Deciphered". New York Times, June 1, 2007.

- ^ "James Watson genotypes, on NCBI B36 assembly". Archived July 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wheeler, D. A.; Srinivasan, M.; Egholm, M.; Shen, Y.; Chen, L.; McGuire, A.; He, W.; Chen, Y. J.; Makhijani, V.; Roth, G. T.; Gomes, X.; Tartaro, K.; Niazi, F.; Turcotte, C. L.; Irzyk, G. P.; Lupski, J. R.; Chinault, C.; Song, X.-Z.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Nazareth, L.; Qin, X.; Muzny, D. M.; Margulies, M.; Weinstock, G. M.; Gibbs, R. A.; Rothberg, J. M. (2008). "The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing". Nature. 452 (7189): 872–876. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..872W. doi:10.1038/nature06884. PMID 18421352.

- ^ Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, June 28, 2003. "Watson Genotype Viewer Now On Line". Archived December 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Press release. Retrieved on September 16, 2007.

- ^ "James Watson's Personal Genome Sequence"

- ^ Watson's personal DNA sequence archive at the National Institutes of Health

- ^ Ian Sample (February 28, 2014). "DNA pioneer James Watson sets out radical theory for range of diseases". The Guardian. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Molenaar, RJ; van Noorden, CJ (September 6, 2014). "Type 2 diabetes and cancer as redox diseases?". Lancet. 384 (9946): 853. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61485-9. PMID 25209484. S2CID 28902284.

- ^ Crow, David (November 28, 2014). "James Watson to sell Nobel Prize medal". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

'Because I was an "unperson" I was fired from the boards of companies, so I have no income, apart from my academic income,' he said.

- ^ Jones, Bryony (November 26, 2014). "DNA pioneer James Watson to sell Nobel Prize". CNN International World News. CNN. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

Watson says he intends to use part of the money raised by the sale to fund projects at the universities and scientific research institutions he has worked at throughout his career.

- ^ "[Watson, James Dewey]. Nobel Prize Medal". Christies.

- ^ "James Watson selling Nobel prize 'because no-one wants to admit I exist'". The Telegraph. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (December 5, 2014). "DNA Laureate James Watson's Nobel Medal Sells for $4.1M". Scientific American.

- ^ "Russia's Usmanov to give back Watson's auctioned Nobel medal". BBC News. December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ "Management Team". UBI. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ^ Teresa Firmino (March 20, 2007). "Nobel James Watson vai presidir ao conselho científico da Fundação Champalimaud". Público (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on March 24, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ Graeme, Chris (December 31, 2010). "Cutting-edge cancer research centre opens in Lisbon". Algarve Resident. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (April 5, 2018). "DNA legend James Watson gave his name to a Chinese research center. Now, he's having second thoughts". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat8024.

- ^ Herper, Matthew (October 8, 2013). "Inside Paul Allen's Quest To Reverse Engineer The Brain". Forbes. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Costandi, Mo (September 27, 2006). "Researchers announce completion of the Allen Brain Atlas". Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Shreeve. J. 2005. The Genome War: How Craig Venter Tried to Capture the Code of Life and Save the World. Ballantine Books, p. 48. ISBN 0-345-43374-2.

- ^ a b Watson, James D. (2007). Avoid boring people: lessons from a life in science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280273-6. OCLC 80331733.

- ^ Steven Shapin, "Chairman of the Bored", Harvard Magazine, January–February 2008

- ^ Charlie Rose Interview, paired with E. O. Wilson Archived October 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine December 14, 2005

- ^ "President of Harvard Resigns, Ending Stormy 5-Year Tenure". The New York Times. February 22, 2006.

- ^ Thompson, C.; Berger, A. (2000). "Agent provocateur pursues happiness". British Medical Journal. 321 (7252): 12. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7252.12. PMC 1127681. PMID 10875824.

- ^ "UK Museum Cancels Scientist's Lecture". ABC News. October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Reich, David. (2019). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-19-882125-0.

- ^ Wagenseil, Paul (March 25, 2015). "DNA Discoverer: Blacks Less Intelligent Than Whites". Fox News. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (October 17, 2007). "Fury at DNA pioneer's theory: Africans are less intelligent than Westerners". The Independent.

- ^ Crawford, Hayley. "Short Sharp Science: James Watson menaced by hoodies shouting 'racist!'". New Scientist. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

... he was 'inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa' because 'all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours, whereas all the testing says not really'.

- ^ Hunt-Grubbe, Charlotte (October 14, 2007). "The elementary DNA of Dr Watson". The Times. London.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (October 17, 2013). "Fury at DNA pioneer's theory: Africans are less intelligent than Westerners". The Independent. London. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Museum drops race row scientist". BBC News. October 18, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ^ Syal, Rajeev (October 19, 2007). "Nobel scientist who sparked race row says sorry — I didn't mean it", The Times. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ "Watson Returns to USA after race row", International Herald Tribune, October 19, 2007.

- ^ Watson, James (September–October 2007). "'Blinded by Science'. An exclusive excerpt from Watson's new memoir, Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science". 02138 Magazine: 102. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

As we find the human genes whose malfunctioning gives rise to such devastating developmental failures, we may well discover that sequence differences within many of them also lead to much of the observable variation in human IQs. A priori, there is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated in their evolution should prove to have evolved identically. Our desire to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so.

- ^ Coyne, Jerry A. (December 12, 2007). "The complex James Watson". Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Watson's folly", Nature, October 24, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ Watson, J. D. "James Watson: To question genetic intelligence is not racism", The Independent, October 19, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2007

- ^ van Marsh, A. "Nobel-winning biologist apologizes for remarks about blacks", CNN, October 19, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ^ "Announcement by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory". The New York Times. October 25, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. October 18, 2007. Statement by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Board of Trustees and President Bruce Stillman, PhD Regarding Dr. Watson's Comments in The Sunday Times on October 14, 2007. Press release. Retrieved October 24, 2007. Archived September 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wigglesworth, K. (October 26, 2007). "DNA pioneer quits after race comments". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 5, 2007

- ^ "Nobel prize-winning biologist resigns", CNN, October 25, 2007. Retrieved on October 25, 2007.

- ^ "Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory James D. Watson". cshl.edu. 2013. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ WebServices. "CSHLHistory – About Us". Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ a b DNA father James Watson's 'holy grail' request May 10, 2009

- ^ Video: BBC 2 Horizon: The President's Guide to Science Archived May 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, September 16, 2008, see 28:00 to 34:00 mark

- ^ "Statement by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory addressing remarks by Dr. James D. Watson in 'American Masters: Decoding Watson'". Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ "James Watson: Scientist loses titles after claims over race". BBC News. January 13, 2019. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ Harmon, Amy (January 11, 2019). "Lab Severs Ties With James Watson, Citing 'Unsubstantiated and Reckless' Remarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ Durkin, Erin (January 13, 2019). "DNA scientist James Watson stripped of honors over views on race". The Guardian.

- ^ Kitcher, Philip (1996). The Lives to Come: The Genetic Revolution and Human Possibilities.

- ^ "Notable Signers". Humanism and Its Aspirations. American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ The Lasker Foundation.1960 Winners Archived July 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on November 4, 2007.

- ^ "Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Achievement in the Sciences Recipients". American Philosophical Society. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ "Double Helix Medals Honorees". Double Helix Medals Dinner. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Anon (1985). "James Watson EMBO profile". People.embo.org. Heidelberg: European Molecular Biology Organization.

- ^ The Hastings Center Archived May 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Hastings Center Fellows. Accessed November 6, 2010

- ^ Nobility News: Honorary Knights 2007

- ^ O'Dowd, Niall. "He Helped Map the Structure of DNA. Up Next is a Cure For Cancer", Irish America magazine, March 10, 2011. Accessed March 22, 2011. "James Watson helped unravel the structure of DNA, a feat so stunning that it is considered the greatest scientific achievement of the 20th century. "

- ^ "John J. Carty Award for the Advancement of Science". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ National Constitution Center.2000 Liberty Medal Recipients. Retrieved on November 4, 2007.

- ^ The National Science Foundation.The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details. February 14, 2006. Retrieved on November 4, 2007.

- ^ "Othmer Gold Medal". Science History Institute. May 31, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "James D. Watson to receive 2005 Othmer Gold Medal". Psych Central. February 23, 2005. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2007 Archived August 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on November 4, 2007.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "University of Dublin, Trinity College".

- ^ Harmon, Amy (January 11, 2019). "Lab Severs Ties With James Watson, Citing 'Unsubstantiated and Reckless' Remarks". The New York Times. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ "Statement by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory addressing remarks by Dr. James D. Watson in "American Masters: Decoding Watson"". Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

In response to his most recent statements, which effectively reverse the written apology and retraction Dr. Watson made in 2007, the Laboratory has taken additional steps, including revoking his honorary titles of Chancellor Emeritus, Oliver R. Grace Professor Emeritus, and Honorary Trustee.

Further reading

[edit]- Chadarevian, S. (2002) Designs For Life: Molecular Biology After World War II. Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-57078-6.

- Chargaff, E. (1978) Heraclitean Fire. New York: Rockefeller Press.

- Chomet, S., ed., (1994) D.N.A.: Genesis of a Discovery London: Newman-Hemisphere Press.

- Collins, Francis. (2004) Coming to Peace With Science: Bridging the Worlds Between Faith and Biology. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2742-8.

- Collins, Francis. (2007) The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4165-4274-2.

- Crick, F. H. C. (1988) What Mad Pursuit: A Personal View of Scientific Discovery (Basic Books reprint edition, 1990) ISBN 0-465-09138-5.

- John Finch; 'A Nobel Fellow On Every Floor', Medical Research Council 2008, 381 pp, ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0; this book is all about the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge.

- Friedberg, E.C.; "Sydney Brenner: A Biography", CSHL Press October 2010, ISBN 0-87969-947-7.

- Friedburg, E. C. (2005) "The Writing Life of James D. Watson". "Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press" ISBN 0-87969-700-8.

- Hunter, G. (2004) Light Is A Messenger: the life and science of William Lawrence Bragg. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852921-X.

- Inglis, J., Sambrook, J. & Witkowski, J. A. (eds.) Inspiring Science: Jim Watson and the Age of DNA. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-87969-698-6.

- Judson, H. F. (1996). The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology, Expanded edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-478-5.

- Maddox, B. (2003). Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-098508-9.

- McEleheny, Victor K. (2003) Watson and DNA: Making a scientific revolution, Perseus. ISBN 0-7382-0341-6.

- Robert Olby; 1974 The Path to The Double Helix: Discovery of DNA. London: MacMillan. ISBN 0-486-68117-3; Definitive DNA textbook, with foreword by Francis Crick, revised in 1994 with a 9-page postscript.

- Robert Olby; (2003) "Quiet debut for the double helix" Nature 421 (January 23): 402–405.

- Robert Olby; "Francis Crick: Hunter of Life's Secrets", Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, ISBN 978-0-87969-798-3, August 2009.

- Ridley, M. (2006) Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code (Eminent Lives) New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-082333-X.

- Anne Sayre, "Rosalind Franklin and DNA", New York/London: W.W. Norton and Company, ISBN 978-0-393-32044-2, 1975/2000.

- James D. Watson, "The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix, edited by Alexander Gann and Jan Witkowski" (2012) Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4767-1549-0.

- Wilkins, M. (2003) The Third Man of the Double Helix: The Autobiography of Maurice Wilkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860665-6.

- The History of the University of Cambridge: Volume 4 (1870 to 1990), Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Selected books published

[edit]- James D. Watson, The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix, edited by Alexander Gann and Jan Witkowski (2012) Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4767-1549-0.

- Watson, J. D. (1968). The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. New York: Atheneum.

- Watson, J. D. (1981). Gunther S. Stent (ed.). The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95075-1. (Norton Critical Editions, 1981).

- Watson, J. D.; Baker, T. A.; Bell, S. P.; Gann, A.; Levine, M.; Losick, R. (2003). Molecular Biology of the Gene (5th ed.). New York: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-4635-X.

- Watson, J. D. (2002). Genes, Girls, and Gamow: After the Double Helix. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-41283-2. OCLC 47716375.

- Watson, J. D.; Berry, A. (2003). DNA: The Secret of Life. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-41546-7.

- Watson, J.D. (2007). Avoid Boring People and Other Lessons from a Life in Science. New York: Random House. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-375-41284-4.

External links

[edit]- James D. Watson Collection at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Library

- DNA – The Double Helix Game from Nobelprize.org

- MSN Encarta biography (Archived 2009-10-31)

- DNA Interactive – This site from the Dolan DNA Learning Center (part of CSHL) commemorates the discovery of the structure of DNA and includes dozens of animations, as well as interviews with James Watson and others.

- DNA from the Beginning – another DNA Learning Center site on the basics of DNA, genes, and heredity, from Mendel to the Human Genome Project.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- James Watson on Charlie Rose

- James Watson at TED

- James Watson at IMDb

- James D. Watson collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- A Revolution at 50, February 25, 2003

- James Watson on Nobelprize.org

- Articles and interviews

- BBC Four Interviews Archived December 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine – Watson and Crick speaking on the BBC in 1962, 1972, and 1974.

- NPR Science Friday: "A Conversation with Genetics Pioneer James Watson" – Ira Flatow interviews Watson on the history of DNA and his recent book A Passion for DNA: Genes, Genomes, and Society. 2002-06-02

- NPR Science Friday "DNA: The Secret of Life" – Ira Flatow interviews Watson on his new book. 2003-05-02

- Discover "Reversing Bad Truths" – David Duncan interviews Watson. 2003-07-01

- Two remembrances of James Watson by one of the founders of molecular genetics, Esther Lederberg, can be found at http://www.estherlederberg.com/Anecdotes.html#WATSON1 and http://www.estherlederberg.com/Anecdotes.html#WATSON2

- James Watson telling his life story at Web of Stories

- American Masters: Decoding Watson PBS film about Watson, including extensive interviews with him, his family, and colleagues. 2019-01-02.

- James D. Watson, Ph.D. Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

- James Watson

- 1928 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American physicists

- 20th-century American zoologists

- 21st-century American physicists

- 21st-century American zoologists

- American atheists

- American biophysicists

- American former Christians

- American geneticists

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American male non-fiction writers

- American science writers

- American textbook writers

- Fellows of Clare College, Cambridge

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Foreign members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Former Roman Catholics

- Harvard University faculty

- Fellows of the Hastings Center

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Indiana University alumni

- Members of the European Molecular Biology Organization

- Members of the Royal Irish Academy

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- American molecular biologists

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- People from Cold Spring Harbor, New York

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Phage workers

- People involved in race and intelligence controversies

- Recipients of the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Scientists from Chicago

- Scientists from New York (state)

- University of Chicago alumni

- Writers from Chicago

- Writers from New York (state)

- American expatriates in the United Kingdom